“And that is how change happens. One gesture. One person. One moment at a time.” – Libba Bray

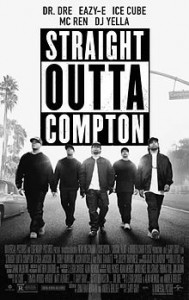

I was bummed when “Straight Outta Compton” received only one Oscar nomination this year. I’d grown up in Compton, had attended Compton High School in the late 1950s, and I‘d also liked the film. Although the young men portrayed in the movie—the soon-to-be-famous rappers of the group, NWA—attended high school in the 1980s, long after the advent of Black Power and after drugs and gangs had begun to dominate the Compton scene, I’d often thought of them as the secretly angry voices of the boys I went to school with in the 1950s. And I’d felt a bond. Though I’m white and female, Compton left me with a rebel edge.

For most of my childhood, I thought of Compton as just an ugly town, its main boulevard crammed with so many glinting car lots that it was hard to tell where one began and the other one ended. Our neighborhood on North Willow St., solidly white and lower-middle-class, consisted of modest houses, small lawns, and one uncontrollably weedy front yard, the latter belonging to a family my parents considered “Okies.” Our own small two bedroom bungalow possessed a living and dining room so minute that one evening, after dinner, my father took a sledge hammer to the separating wall to create a decent living room. After that we ate in the kitchen.

Compton was a place I longed to distance myself from, but my family life had left me so emotionally fragile that I could only take leave of Compton in the mildest of fashions. I read brooding books that I was too young to understand—The Brothers Karamazov, for example, which I took from the local library’s list of “100 Best Books.” I went to the beach when I could, though it required a long drive past dried fields and aging oil rigs, the acrid smell of petrol filling my nose, and sometimes my best friend and I would ride horseback at stables near the L.A. River, which hadn’t been cemented over then and which was rumored to have quicksand along its banks. We rode bareback through the brush and trees to feel adventurous and free, which we weren’t of course, since both our family lives were laced with pain. My home, in fact, was a place I longed to escape as well, but where could I go? The only place I knew of was school, and it was school, and Compton High School, in particular, that gave my rebellious energies a new direction.

Compton was a place I longed to distance myself from, but my family life had left me so emotionally fragile that I could only take leave of Compton in the mildest of fashions. I read brooding books that I was too young to understand—The Brothers Karamazov, for example, which I took from the local library’s list of “100 Best Books.” I went to the beach when I could, though it required a long drive past dried fields and aging oil rigs, the acrid smell of petrol filling my nose, and sometimes my best friend and I would ride horseback at stables near the L.A. River, which hadn’t been cemented over then and which was rumored to have quicksand along its banks. We rode bareback through the brush and trees to feel adventurous and free, which we weren’t of course, since both our family lives were laced with pain. My home, in fact, was a place I longed to escape as well, but where could I go? The only place I knew of was school, and it was school, and Compton High School, in particular, that gave my rebellious energies a new direction.

Until tenth grade I lived in all white neighborhoods and attended all white schools, but when race covenants barring nonwhites from the city’s center were finally overturned, middle-class blacks and Latinos began moving into town. By the time I entered Compton High, the changing demographics of Compton were suddenly visible, and, from the beginning—-one gesture, one person, one moment at a time-—the inequalities of Compton High got under my skin. Despite the changing population of the school, college prep classes were filled almost entirely by whites. The same was true of student government, of many clubs, and of song, cheer, and flag leaders as well. The sports teams were a different story. Bill, the young black man I knew best, a track star and a member of the football team, wrote in my yearbook, “To the best girl at Compton High.” Somehow, over the great distance between us, we’d formed a tie.

In the fall of my senior year, Hector, a smart and serious Mexican-American student with a long history of school service, was passed over for admission to the elite senior service club. I, who had been chosen, was shocked at the snub. My half-Chinese, half-Mexican sorority sister, Grace, clearly the most graceful and shapely of all the girls trying out for the flag team that fall, was passed over as well. When the announcements were made, I saw Grace bursting into tears, her head in her hands, her shiny black hair falling forward. We all knew why she wasn’t chosen. I was angry and hurt on her behalf but had no notion of protest or struggle.

I was happy when Grace was elected Prom Queen later in the spring, but I was also puzzled by the reversal of her fortunes. Then I figured out that flag and song girls were chosen by an all-white selection committee, Prom Queens by a schoolwide election. Students of color had block-voted. It was the first time I understood that marginalized people could come together to change the world. When the following year, a black young woman was elected Prom Queen for the very first time, I understood that changes in power were taking place—at least at Compton High. As a freshman at Stanford that year, which I was attending on a scholarship, I was by struck by the fact that there were only two black students in my class: one young man and one young woman. And I would be cynical enough to assume that Stanford had admitted them as a pair—so they could date each other.

Four years later, as a graduate student at U.C. Berkeley, I would read James Baldwin’s “Down at the Cross,” and my life would change. Baldwin gave form to a thought I’d vaguely entertained as an undergraduate reading Sartre in the woods at Stanford—that an engaged and passionate life was the only life worth living, that one needed to have a cause. The cause Baldwin lived for was the “unconditional freedom of the Negro,” and I had never read anyone who wrote so passionately about the “horrors” of black life or who dared talk about the moral bankruptcy of most whites who were so “far from models of how to live” that they were “unable even to envision” the changes that must be made. I thought about Compton High, about Hector, Grace, and Bill, about the scores of black students who had passed through it without receiving the few benefits and powers that it offered, and I saw that I too had been “unable even to envision” how deep the changes had to be.

Under the cathedral like ceiling of Berkeley’s Doe Library Reference Room, my view of history and myself underwent an alteration and Baldwin’s cause became my own. I joined the Civil Rights Movement, knocking on doors to register black voters in nearby Oakland, and, in the years to come, joined many movements for social change. But it was not just Sartre or the Sixties that had prepared me for this moment of transformation. It was being from Compton as well

As I watch the Oscars this year, it’s a foregone conclusion that talented people of color will be passed over once again. It will make me angry—and it will feel personal. I’m straight outta Compton—still.