In memory of my dear friend, Mary, the magical “Claire” of my memoir who died Sunday, June 15, of a brain tumor, I am re-posting this chapter from my memoir, Tasting Home.

Before I entered the women’s group at Penn, I didn’t much trust other women. (Mother had left me wary about members of our sex.) In the end, I would have a long history with such groups—and the menus would become increasingly elaborate– but it was Claire who prepared me, who first opened me to the love and care of women.

Before I entered the women’s group at Penn, I didn’t much trust other women. (Mother had left me wary about members of our sex.) In the end, I would have a long history with such groups—and the menus would become increasingly elaborate– but it was Claire who prepared me, who first opened me to the love and care of women.

Sometime in 1966, when we were still in Berkeley, Jake had presented Dick and me to the new woman in his life, Claire. Claire had a fragile elegance that was very appealing. She wore glamorous, sometimes vintage, clothes—a pair of forties-style white pants, say, with a beige, loose-sleeved blouse printed in muted, rosy flowers. Her heavy hair, the color of dark honey, hung well below her shoulders. The thinnest of eyebrows floated about her long, large, hazel eyes. And her voice was whispery, as if full of secrets you’d like to share.

Claire was finishing her B.A. in the English department where she also worked as part-time secretary, but these realities seldom surfaced as topics in our conversations. What she did like to talk about were her ever-changing passions. She studied piano, always on a baby grand. “I never rent anything but a baby grand,” she’d say, her eyes widening. “The music sounds sooo much better.” At other times she took classes in watercolor, ballet, poetry, or Greek. To career-minded graduate students like Dick and me, the time Claire invested in these studies did not seem entirely practical (poetry, of course, being an exception!) Only later did I understand that baby grand pianos, watercolor, and Greek were at the heart of something magical about Claire. She had a gift for transforming ordinary life into something beyond the ordinary, into something that took hold of you despite the accompanying eccentricities.

Although Claire laughed easily and had a self-deprecating sense of humor that was endearing, there was something sorrowful about her too. Her mouth turned down at the corners when her face fell into repose. In time I came to know what lay behind that mouth. Claire’s mother had died when she was three years old, and her already-distant father had quickly turned to alcohol and abuse. “I want you dead,” he’d shout at her. The last time he beat her she had been nineteen, and the beating had lasted two hours. For three days after Claire was unable to speak.

The pain and loneliness of those early years never left her. But by the time we came into each other’s lives, Claire had a strategy for dealing with the Dickensian brutalities of her past. She created, and recreated when necessary, an exuberant and enticing self, an exciting alternative existence that was as deep a part of her as the sadness and the more mundane realities of attending undergraduate classes and doing part-time clerical work. The glamour of this alternative life was partly expressed in the thoughtfully achieved allure of her appearance and in her cultivation of graceful practices such as dancing ballet and reading classical texts, but it was also embodied in the sumptuous meals she cooked for friends and in the charming, off-beat surroundings in which she prepared and served them. When you stood in Claire’s kitchen or sat in her dining room, wonder, glamour, and comfort became part of your life too.

In 1968, all four of us moved East. Dick and I began our jobs in Philadelphia. Jake became a professor in New Jersey and Claire, who had married Jake the year before, found work in the rare book room of the university where Jake was employed. Jake had been our best friend since 1963, and now Claire was too. But Claire, to me, became something more. Since childhood I had had a recurring dream: I revisit a familiar house, opening door after door until I find a room—the room that I have been looking for without knowing it-—and it appears so beautiful and so compelling that I am deeply comforted. Every home that Claire created had a similar effect on me. When Dick and I visited Jake and Claire, we stayed in a guest room decorated by Claire with painted white furniture and brown, flowered, calico sheets. I slept so deeply in those rooms that sometimes I didn’t awake until one in the afternoon.

Why I felt so comforted and secure was not entirely clear. Perhaps it was the way the exuberance of Claire’s hospitality, her artful attention to the beauty of the rooms in which her guests slept, sat, and ate, her delight in feeding us delicious meals, evoked and partially compensated for the motherlessness of both our lives. In Claire’s childhood home the wondrous, feeding mother of her infancy had disappeared forever, and in mine the mother who did feed, and overfeed, was otherwise absent and rejecting. In creating elegant rooms, in preparing comforting meals, Claire mothered herself but she mothered her friends as well. It was Claire who showed me that in becoming the wondrous, nurturing mother one might find a path to recovering something of the parent one had lost, or to healing wounds that were left by parents who couldn’t or wouldn’t love us as we needed to be loved.

Claire’s dwellings were always rented, but she had a gift for finding places with some charming feature and then making them seem alive, enchanted, full of possibilities. There was the farmhouse in the Pennsylvania countryside that looked out onto snowy fields.

“Can I paint?” Claire asked the owner.

“No painting,” the landlady replied. She was a regal woman with a tweed jacket and white hair.

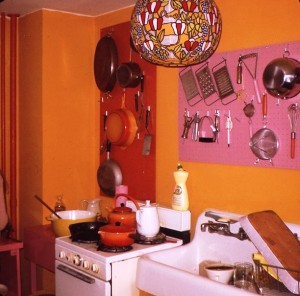

Claire couldn’t bear the dark-paneled walls, so she covered them with white burlap and hung dark orange-flowered curtains on the windows. A few weeks later, she defied the landlady and painted the kitchen the color of an open cantaloupe. (The kitchen walls were plaster, Claire explained to me. “It’s not like I’ve painted over wood paneling.”) Then she enameled squares of peg board in darker orange and neon pink and hung them on the walls to hold her pots and pans. The effect was dazzling. When you stood in that kitchen, the dark fragrance of boeuf bourguignon filling the air, you knew you were alive no matter how bleak the weather outside or within.

Claire and Jake moved to New York a year later where Claire found an apartment with an arched window in the dining room. She painted the room golden yellow and hung small, colored drawings of fruit on the walls. She had acquired a round butcher block table by then (it was enormous and seated eight), and she painted its base with the white, Swedish enamel she had come to swear by. She coated her old, spindle-backed chairs with the same shiny white so the furniture seemed to float in a world of gold. White iris in a white pitcher balanced on the table surface, and one evening the four of us floated there with the furniture and ate tacos de crema. The tortillas were fried and dipped in light cream sauce, then folded to hold sour cream and chiles and molten Monterey jack cheese. For dessert she served pears poached in a bottle of red wine that had been reduced to a thick syrup. The pears, in their ruby sauce, smelled like cinnamon and looked so much like a still life that I took their picture.

After dinner, while Dick and Jake lolled in the living room with its floor-to-ceiling white bookcases and white couches, sipping Drambuie and talking of Renaissance poetry, Claire and I slipped away to contemplate the rest of the apartment. We moved slowly as if tasting the rooms.

“Should I repaint the dining room?” Claire asked.

“Why? I think it’s beautiful just the way it is.”

Claire’s mouth grew firm. “I want it to be more . . . intense,” she said. “I’m thinking aubergine.” She would repaint that dining room seven times. “My favorite was the aubergine,” Claire would say to me, long after she no longer lived in New York.

***

In 1976, Jake took a position in Rhode Island, and he and Claire rented the top floor of a cottage in Narragansett that stood just above the Atlantic shore. Claire’s dining room in the cottage was entirely enclosed, though little nooks led off from it, ending in gabled windows that opened to views of the water. Claire had placed chairs and small tables in each nook as if someone in the house might be inclined to watch for ships or whales or something new on the horizon.

“Judy,” Claire called to me as soon as I came in the door. “Come, look. You can see the ocean when you stand at the sink.” For Claire there was always something beyond, something she longed to reach.

The dining room that night felt like a captain’s quarters, rounded, snug, with the white bookcases and soft lamps. Claire had placed rust chrysanthemums in the white pitcher and we sat at the butcher block table on our white chairs, as if suspended this time over the sea itself. We ate chicken breast volaille with morels and Madeira in a sauce of egg yolk, cream, and cheese. “I only use the dried morels,” Claire told me. “They have more flavor.” Again we ate the pears in pools of thickened wine. When I think of that evening now I feel a fullness in my throat and chest. It is the ache of my desire to return, just for a moment, to savor the comfort and content I felt that night, the sense of possibilities in that dining room, that dinner, the ocean, our friendship, in Claire herself.

The next year Jake took a job in Chicago and Claire, who was working for a sports publicist, remained in New York. They flew to see each other on weekends, but the effort was hard to sustain. The year after, Claire fell in love with a man in her ballet class and eventually she called Jake to ask for a divorce. Jake agreed, and a few months later, the man from ballet returned to his previous girlfriend. Claire moved on, finding work in a music store where well-known musicians and composers were taken by her charm.

Claire and I wrote to each other. We called, but our lives were changing. Without our four-way friendship, our lovely dinners in her many dining rooms came to an end, taking on the fragile, shimmering quality of memory and myth. Eventually, I would buy my own butcher block table and paint the base with a wash of turquoise instead of white. I would dress my guest bed in the calico sheets that Claire favored, but mine would be green, not brown, and I would paint my dining room the color of celery and then lemon yellow. (I wouldn’t be satisfied with the yellow but two repaintings would be enough for me.) I would serve my guests boeuf bourguignon, tacos de crema, chicken volaille, and pears in red wine. Though I never came close to Claire’s elegance, her strategies for self-renewal and for sharing with others the life and comforts she created stayed with me.

Sometimes it seemed to me that the very deprivations of Claire’s life had given her an unusual capacity for new, often fanciful, kinds of growth. No matter what life brought—a mother dead too soon, an abusive father, a faithless lover, divorce from the princely Jake—for Claire there was always the possibility of going on, of reinventing glamour, wonder, comfort for herself and others. Claire’s inventiveness, the enchanted spaces she created, the delicious dinners she cooked for friends, were like what Raymond Williams calls those inexplicable flowerings of love and energy that brighten a Dickens novel. I would turn to these resources time and time again as a respite from my own anxieties and despair.

____________________________________________________________________________

Pears Poached in Red Wine

(Adapted with permission from racheleats.wordpress.com. Photo from racheleats.wordpress.com)

6 firm medium-sized pears (Bartlett or Williams work well)

A big bowl of cold water with the juice of half a lemon squeezed in it

7 oz water

A bottle of young red wine such as a good Pinot noir or cote-du-rhone ( don’t stint on the quality of the wine)

2 ½ c sugar

A stick of cinnamon

2 cloves

A strip of lemon peel

1. Peel pears leaving the stem intact. Drop each pear into lemon water while you peel the next to prevent discoloration.

2. Put the wine, 7 oz. water, sugar, cinnamon, cloves and lemon peel in a large heavy pan and bring to a gentle boil over a medium flame. Keep stirring until the sugar is dissolved.

3. Carefully lower pears into the simmering water.

4.Cover the pan and allow the pears to simmer for 25-40 minutes until they are tender and translucent, but not soggy, when pierced with the point of a knife.

5. Remove the pan from heat, leave it covered, and let pears cool in the cooking liquid.

6.Once the pears are cool, lift them from the liquid and set aside while you reduce liquid to about half the original and into a thick, dense syrup.

7 .Reunite the pears with the syrup and allow them to sit for a day, and preferably two or three, turning them every now and then. (I refrigerated the pears. Serve the pears in their remaining syrup. Add cream if you like.

This is a wonderful eulogy to Claire. I wish I had known her.

She brought glamour and comfort to so many lives. I wish you had known her.

I remember Claire from your memoir. How wonderful that you took those pictures and saved them all these years. What a beautiful post and tribute to Claire.

Thank you, Valorie. As you can imagine, I treasure these old pictures. I can revisit those dining rooms and kitchens and feel what I once felt.

What a wonderful tribute to a lovely lady! I just finished reading your book. For months I’ve been grumpy because I hadn’t read a book of late that I could sink my teeth into, wallow in, and devour in a few sittings. Well! Thanks to you, I am grumpy no more. If this book was a meal, pun intended, I devoured it whole. I identified with so much of it. Your parent’s withdrawal from love, your interweaving of the times you lived in, and how cooking played a part, and finally, your coming full circle, accepting life and what it has to dish out (again-pun intended). It’s amazing what we have to go through in order to attain wisdom. Wisdom comes to us on the other side of suffering. Sometimes when I hear someone give an opinion, etc., I dismiss it in my mind by thinking, “Just wait until life teaches you about life.” If you live long enough, it certainly will. I look forward to your posts. As Anne Shirley would say, “I have found a kindred spirit.”

Dear Katherine, Thank you so much for these kind words about Tasting Home. And I love the allusion to Anne Shirley, my favorite girlhood character. Just because you use the phrase “kindred spirit,” I can tell you are one. Readers like you make it all worth while.

If you are so inclined, I would love it if you put a few lines of this into an Amazon review.